The Precarious Balance: Are Public Interest Litigations Still Serving Their Purpose in India?

Recently, the SC dismissed a PIL seeking to halt the deportation of the illegal Rohingyas and expressed frustration over repeated PILs without any substance. We explore roots & dynamics of PIL.

Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in India stands as a distinctive feature of its legal landscape, born from a period of judicial activism aimed at democratizing justice. Initially conceived as a powerful tool to provide legal recourse to marginalized communities and address pressing public concerns, PILs have evolved significantly since their inception. This article delves into the multifaceted role of PILs in contemporary India, examining whether they continue to fulfill their intended purpose amidst growing concerns about their misuse as political instruments and in matters impinging on national security. The recent frustration expressed by the Supreme Court regarding repeated PILs seeking to halt the deportation of Rohingya Muslims serves as a poignant example of the complexities and challenges surrounding the use of this unique legal mechanism.

The Genesis and Golden Era of PILs: Fulfilling the Promise of Justice

The concept of Public Interest Litigation traces its origins to the United States in the 1960s, where it emerged as a means to offer legal representation to underprivileged sections of society. India embraced this concept in the late 1970s, with the landmark case of Hussainara Khatoon vs. the State of Bihar in 1979 often cited as the genesis of PIL in the Indian judicial system. This case, where lawyers filed on behalf of undertrial prisoners languishing in jail for extended periods without trial, marked a turning point, leading to the release of thousands and establishing PIL as a potent instrument for public interest advocacy.

The introduction and subsequent evolution of PILs in India are largely attributed to the judicial activism of the Supreme Court, with Justices V.R. Krishna Iyer and P.N. Bhagwati being the pioneers of this transformative legal mechanism. Justice Bhagwati, often referred to as the "father of PILs" , championed the idea that the judiciary had a crucial role in ensuring justice reached all citizens, irrespective of their socio-economic status. The core objectives of PILs were to vindicate the rule of law, facilitate effective access to justice for the socially and economically weaker sections of society, and ensure the meaningful realization of fundamental rights. This was achieved by relaxing the traditional rule of 'locus standi', which previously restricted the right to approach the court to only those whose own rights were directly infringed. This relaxation allowed any public-spirited individual or organization to approach the court on behalf of those unable to do so themselves or for matters of broad public interest.

The initial years of PILs witnessed significant successes in addressing systemic injustices. Landmark cases, beyond Hussainara Khatoon, such as those concerning environmental protection led by M.C. Mehta , and cases fighting for the rights of bonded laborers and women demonstrated the immense potential of PILs to empower the powerless and give voice to marginalized groups. The judiciary's interpretation of the right to life under Article 21 expanded to include dignity, health, education, and a clean environment. Cases like Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan redefined workplace ethics by laying down guidelines against sexual harassment. This initial success solidified the belief that the judiciary could be a significant force for social change in India, addressing issues that often eluded the attention or action of the executive and legislative branches. PILs became a vehicle for social justice and activism.

The Shadow of Misuse: PILs as Tools for Political Agenda and Harassment

Over time, however, concerns have mounted regarding the misuse of Public Interest Litigations. What was once envisioned as a mechanism for public good has increasingly been employed for personal gain, publicity, and to further political agendas or harass opponents. The very term "Public Interest Litigation" has, in some instances, seemingly morphed into "Publicity Interest Litigation" or "Private Interest Litigation". The spirit behind PILs has been distorted, with the tool being used for harassment, publicity, personal gains, business interests, and corporate gains. For instance, in Kalyaneshwari vs Union of India, the court noted the misuse of PIL in business conflicts where a petition seeking the closure of asbestos units was found to be at the behest of rival industrial groups.

Judges and legal experts have voiced their apprehension about this trend, noting that the original social justice vision of PILs is being increasingly overshadowed by petitions filed with ulterior motives. Serial litigators have been known to file numerous PILs on a wide array of matters. Furthermore, there are instances where PILs have been allegedly used as a tool to target infrastructure projects, potentially for purposes of blackmail or to stall development. The Supreme Court observed that PILs are increasingly used to target infrastructure projects and can become tools for blackmail . This shift in the application of PILs threatens to undermine the credibility of the mechanism and divert crucial judicial resources away from addressing genuine public grievances. The Supreme Court itself has acknowledged the increasing misuse, observing that PILs are sometimes used for private or political interests. Solicitor General Tushar Mehta even referred to some PILs as "professional PIL shops".

The Judiciary Under Strain: The Impact of Frivolous PILs

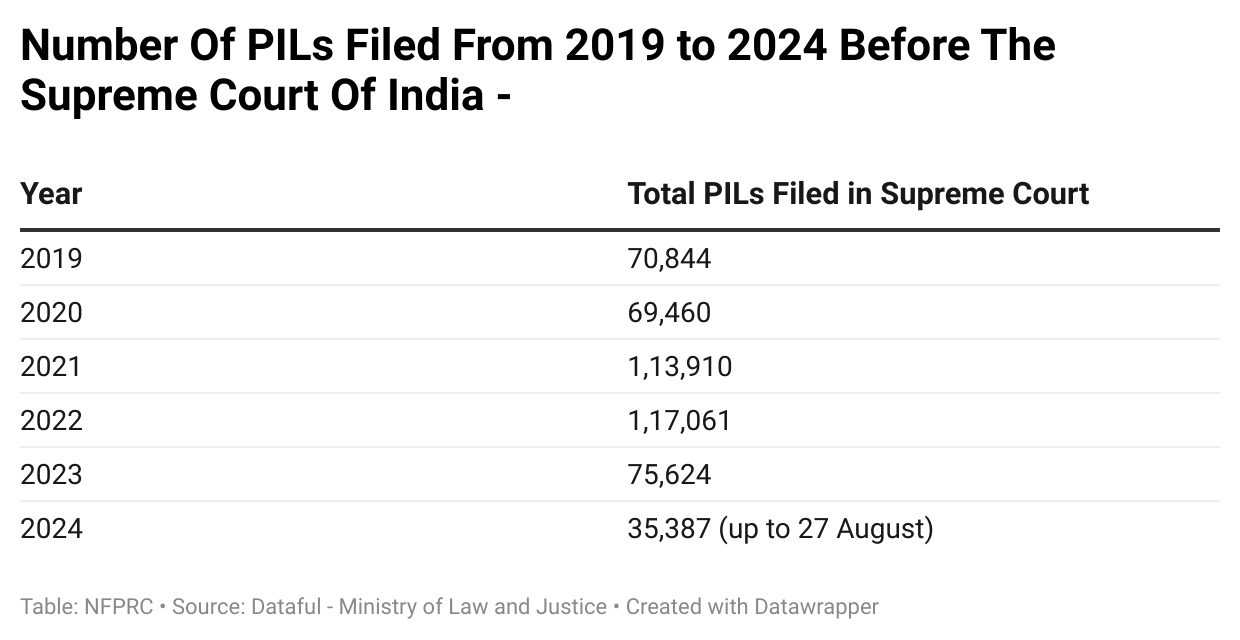

The surge in the number of PIL filings over the years has placed a significant burden on the Indian judiciary, which already grapples with a substantial backlog of cases. The sheer volume of PILs filed annually is staggering. Data from the Supreme Court indicates a significant increase in filings over the years.

A substantial portion of these filings are alleged to be frivolous, filed for personal vendetta, publicity, or political motives, thereby wasting valuable judicial time and delaying justice for genuine cases. Frivolous PILs can also lead to the erosion of public trust in the judicial system. The Supreme Court has, on multiple occasions, expressed its concern over this misuse and has issued guidelines to try and curb the filing of frivolous PILs. Furthermore, the courts have not hesitated to dismiss petitions deemed frivolous and even impose fines on the petitioners. For example, the Delhi High Court dismissed a PIL seeking an investigation into the Delhi government's COVID-19 relief funds, noting the petitioner relied on a tweet without proper research and imposed a fine. In another instance, the Supreme Court imposed a hefty cost of ₹5,00,000 on a petitioner for filing a frivolous PIL questioning the oath taken by the Chief Justice of a High Court. However, despite these measures, the problem persists, highlighting the challenge in distinguishing between genuine public interest and mala fide intentions. The rise in frivolous PILs is a grave concern as courts end up wasting time that could be used for constructive purposes.

National Security vs. Public Interest: The Supreme Court's Balancing Act in Rohingya Deportation Cases

The case of repeated PILs filed to halt the deportation of Rohingya refugees brings to the forefront the delicate balance the Supreme Court must strike between national security concerns and the principles of public interest and humanitarian obligations. The Supreme Court expressed its irritation with the repeated attempts to file PILs on the same issue, especially without the presentation of any new facts. This reaction suggests a potential limitation of PILs when they intersect with matters of national security as perceived by the government.

The government's stance in the Rohingya issue is that they are illegal immigrants who pose a threat to national security. India, notably, is not a signatory to the UN Convention on Refugees , which impacts its international obligations regarding refugee protection. On the other hand, the petitioners argue based on humanitarian grounds, citing the persecution faced by the Rohingya in Myanmar and alleging forced deportations and inhumane treatment by Indian authorities, including being forced into the sea. The UN has also expressed alarm over reports of such actions and emphasized the principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits returning individuals to a territory where they face serious threats.

This scenario highlights the inherent tension when PILs, designed to protect fundamental rights and public interest, are pitted against the government's perception of national security imperatives, particularly concerning non-citizens. The Supreme Court's reaction suggests a cautious approach when dealing with such sensitive matters, potentially indicating a deference to the executive's judgment in areas of national security.

Revisiting the Purpose: Are PILs Still a Mechanism for Public Good ?

Considering the evolution of Public Interest Litigation in India, it is evident that while PILs have been instrumental in achieving significant social justice outcomes and holding the government accountable , their effectiveness is increasingly challenged by their misuse. The original intent of providing access to justice for the marginalized seems to be getting diluted as the mechanism is increasingly used for extraneous purposes, including political gains and harassment. While PILs have undoubtedly brought about transformative changes in India's judicial landscape and empowered citizens to seek justice, the growing trend of misuse raises serious questions about their continued efficacy in serving the public good. The original promise of PILs, rooted in social justice, has faced challenges. Some argue that the initial objective of defending the disadvantaged has been lost. The rise of "Publicity Interest Litigation" and "Private Interest Litigation" indicates a deviation from the core purpose .

Way Forward: Safeguarding the Integrity and Effectiveness of PILs

To ensure that PILs continue to serve their intended purpose, several measures need to be considered. Stricter scrutiny of petitions at the initial stage is crucial to filter out frivolous or malafide filings. Uncertain and doubtful PILs should be rejected at the initial screening phase. The courts must be fully satisfied that substantial public interest is involved before entertaining a petition. Verifying the petitioner's credentials and ensuring the absence of personal, private, or ulterior motives is essential. Imposing significant penalties on those who file baseless PILs could act as a deterrent. Some suggest imposing hefty costs on frivolous petitions to make it restrictive in the future. For instance, the Supreme Court imposed a cost of ₹25 lakh on an activist for filing a PIL challenging the shifting of a mini-Vidhan Sabha, deeming it an abuse of the PIL concept. Promoting greater awareness about the responsible use of PILs among the public and legal fraternity is essential. Educating the public about the true purpose of PIL and the consequences of misuse can help. The judiciary must remain vigilant in ensuring that PILs are used for genuine public interest and not for ulterior motives. There is also a case to be made for potential legislative measures to provide a more structured framework for the filing and adjudication of PILs. Establishing formal rules for supporting genuine PILs and discouraging others is recommended. Encouraging the use of alternative dispute resolution procedures might also help reduce the burden on the courts. Lawyers should actively refuse to represent malicious petitioners and abide by professional ethics. The media also has a role in highlighting cases of PIL abuse. The number of petitions filed by an individual petitioner could be limited. The Supreme Court has also suggested that PIL practitioners should provide an undertaking to recover damages if their PIL is dismissed.

Conclusion: Reaffirming the Role of PIL in India's Constitutional Framework

Public Interest Litigation remains a vital component of India's constitutional framework, offering a unique avenue for social change and ensuring that the voices of the marginalized are heard within the legal system. Its initial promise of democratizing justice and holding power accountable has yielded significant benefits for Indian society. However, the increasing instances of misuse, particularly for political agendas and in sensitive matters of national security, pose a threat to the very purpose and integrity of this mechanism. Safeguarding the effectiveness of PILs requires a concerted effort from the judiciary, the legislature, and the public to promote their responsible use and prevent their degeneration into tools for personal or political ends. Only through such efforts can PILs continue to serve as a beacon of hope for justice and uphold the principles enshrined in the Indian Constitution. The need of the hour is for the courts to follow the law without exception and deter litigants from filing motivated petitions. The true essence of PIL must be preserved to ensure it remains a tool for those who genuinely need it.